“Anyone can convict the guilty, someone who is innocent, now that is something special.”

Dark humor such as this is commonplace in the blood sport known as criminal jury trials. Nowhere are the stakes higher and the combatants more competitive. Judges often complain about the level of animosity between defense lawyers and prosecutors. Defense lawyers are seen as obstructionists trying to get the guilty off, and prosecutors are purveyors of pain demanding unjust convictions and cruel sentences. Remarkably, these comments come from a reasonably healthy criminal justice jurisdiction where the defense still has the heart to fight back.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, last year there were a record number of wrongful convictions reversed, 149, which is 10 more than in 2014 and higher than any other recorded year. Since the group began keeping records in 1989, there have been more than 1730 such documented cases. These miscarriages of justice are no small matter, these are serious cases in which people’s lives were entirely taken from them, families destroyed, children taken from their parents. The scientific breakthrough of DNA testing is responsible for most of these exonerations. But what if there is no DNA evidence, which is usually the case, how many men and women sit in prison for a crime they did not commit with no magic bullet to prove their innocence? Does anyone care?

Witnesses may recant their testimony, even explain their motive for lying, new evidence of innocence may be discovered, and of course the most common false convictor, yes, the jail house snitch is a liar, he did make up a story to get his sentence reduced, he’d done it before and he’d do it again. Countless Writs of Habeas Corpus that present this kind of exonerating evidence are almost always opposed by prosecutors and routinely denied by judges. To admit the system made a mistake is an attack on its credibility, the inherent presumption of guilt, a serious blow to the conviction machine. In a rare instance when a judge has the integrity to grant a hearing to publicly test the evidence, the games begin.

I spent months in one such hearing where the evidence of innocence was overwhelming but that didn’t slow the prosecution. It is one thing to try a case, but to come along later and say you got it wrong, take away one of their wins, that’s when it gets ugly. Fortunately, we had a courageous judge, not up for re-election, and an innocent man was released after five years at Pelican Bay on a 44 to life sentence.

What happened in my case is rare. We had the assistance of honest and dedicated law enforcement personnel from another jurisdiction that helped balance the scales. Most prisoners have no such resources, they are the poorest of the poor, and until recently no one would help them. DNA changed that; today innocence projects have sprung up across the nation, thus the reason for all the exonerations. It is long overdue, and they are just getting started.

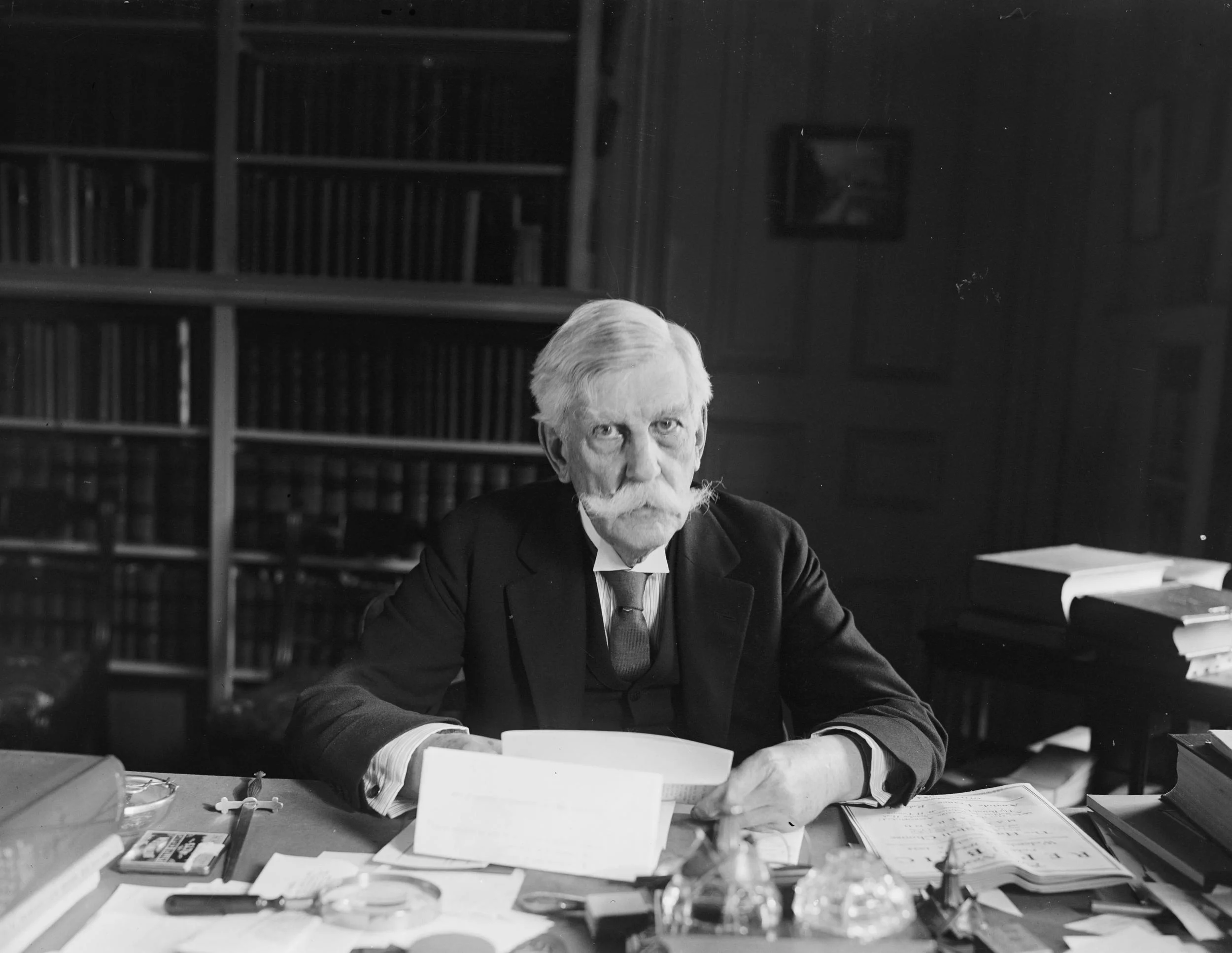

Chief Justice Oliver Wendall Holmes once said, “It is better to have a criminal justice system that acquits 100 guilty men, than one that convicts one innocent.” This is the most noble of sentiments, once spoken by the highest judge in the land. May we never forget this wisdom, for if we do, none of us are safe.